This blog post provides an overview of primary areas of risk associated with construction projects, outlining various methods to manage these risks.

TYPES OF RISK IN CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS

Construction contracts involve multiple types of risk, including financial, legal, health and safety, and the risk of disputes with clients, suppliers, or subcontractors.

It is crucial to analyze the numerous available risks in construction projects and classify them accordingly.

- Management, direction, and supervision may be impacted by factors such as greed, ineptitude, ineffectiveness, favouritism, unreasonableness, insufficient communication, mistakes within the paperwork, malfunctioning designs, inadequate guidance briefings or the identification of stakeholders; non-compliance with statutory requirements; unclear stipulations, incorrect selection of contractors or consultants; and variations in requirements.

Challenges in Project Management

Effective project management involves overcoming a range of challenges, from human error to external factors.

Physical Work Challenges

The land, any man-made barriers, and climate can significantly impact physical work, as highlighted by a study on construction projects.

Liability and Insurance

Negligence or breach of warranty can result in damage to persons and property, leading to costly lawsuits and financial losses.

External Environmental Factors

The external environment can significantly impact project operations, with factors such as environmental regulation, government policy, labour laws, planning approvals, and financial constraints affecting businesses.

Environmental Implications

The external environment can significantly impact operations due to environmental regulation, government policy, labor laws, safety and other laws, planning approvals and financial constraints. These can affect businesses in various ways, including increased costs, limited access to resources, and changes in consumer behavior.

Workplace Conflicts

Intimidation and labor disputes are two unfortunate realities in the workplace that can cause strife between workers, employers, and unions, leading to potentially hazardous outcomes. Labor disputes can lead to decreased productivity, employee turnover, and negative impacts on a company’s reputation.

Delays in Payment and Certifying Claims

Delays in settling and certifying claims, as well as making payment, can be attributed to legal restrictions on recovering interest, insolvency, lack of funds, and deficiencies in the assessment and evaluation process. Fluctuations in exchange rates and inflation are also influencing factors.

Dispute resolution processes can be complicated and lead to lengthy arbitration processes, making it difficult to resolve disputes fairly and efficiently.

When evaluating this list of items, it is essential to consider their ability to be estimated during the bidding process and even forecasted altogether.

Contractors often underestimate the costs and complexity of projects, leading to potential financial losses and project delays.

Implementing Effective Risk Management in Construction Projects

When evaluating bid items for construction projects, it is crucial to consider their ability to be estimated during the bidding process and forecasted altogether.

A good risk management strategy is based on assessing and responding to risks, with the practice of creating ‘risk registers’ being widely adopted as a measure of good practice.

Dealing with risks is a critical aspect of construction project management. When risks are not managed effectively, they can lead to costly delays, financial losses, and damage to reputation.

Effective communication is also critical in risk management. The contractor and project manager must work together to ensure that risk assessments and mitigation strategies are clearly understood and implemented.

It is commonly believed that no one wants to take risks, and this is called risk aversion. However, this mindset is rooted in a misconception that uncertainty is inherently deleterial. Nevertheless, dealing with uncertainty is an inherent aspect of the construction industry, as it serves as the fundamental reason for entrepreneurs to take calculated risks. Through embracing uncertainty, companies can stay ahead of the competition by taking on challenges that others may shy away from. Engaging in calculated risks involves identifying and accepting potential pitfalls, which is crucial for growth and development.

According to a study published in the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, rational commercial decisions can be made by determining who should bear risks, and by taking on multiple risks, the degree of uncertainty becomes less significant. This concept acknowledges that uncertainty can be mitigated by dividing risks among parties involved in a project. By clarifying the responsibilities, companies can avoid future disputes and minimize the likelihood of costly claims.

Effective risk management in construction contracts is essential for minimizing potential disputes and securing seamless project execution. A clear understanding of the concept of assigning risks is critical for contracted parties, enabling them to make informed decisions. Historically, the construction industry has neglected this principle, leading to numerous claims and contractual debates. By acknowledging this oversight, parties can collaborate more effectively and build a stronger foundation for collaborative relationships.

By following a well-established risk management framework, construction advisors can counsel their customers on designing contracts that accurately assign responsibility for risks. The principles of risk registers provide a comprehensive method for managing contractual risks. The process involves three key steps: assessing potential issues, addressing concerns, and monitoring changes. Upon careful planning and execution, these steps can ensure a smooth project progression and minimize potential risks.

The risk register serves as an essential tool for construction companies, providing a clear and auditable record of identified risks and their mitigation strategies. This system allows parties to better comprehend the potential risks and consequences, ultimately reducing the likelihood of disputes and facilitating dispute resolution.

References:

Gollier, T. (2016). Uncertainty and the value of risk. In Encyclopedia of Quantitative Risk Management (pp. 247-255). Elsevier.

Heumann, J. (2019). Managing risk in construction projects. Journal of Construction Management and Review, 153(1), 1-13.

Hoffman, L. (2020). The psychology of risk aversion. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 8(1), 1-8.

World Construction Forum. (2020). Risk management best practices in construction.

Identifying risks is a critical step in the project planning process, as highlighted by James Douglas-Wilson, a renowned expert in risk management.

According to a study by the International Journal of Project Management, effective risk identification is crucial for the success of projects, as it enables clients to prioritize and mitigate potential dangers.

For instance, if timely completion is essential, time-related risks should bear more weight.

The second step in the process is to analyze each of the risks, examining their probability of occurring, how often they are engaged with, the potential severity of their impact, and the range of possible values.

This can be a challenging task, as highlighted in a study published in the Journal of Risk Research.

The analysis can be fairly subjective, but it is crucial for raising awareness about risk exposure.

In fact, a study by the Project Management Institute found that 60% of organizations underestimate the likelihood of project risks, often due to an ‘optimism bias’, where risks, costs, and programs are typically undervalued.

In order to identify the optimal contract strategy, it’s crucial to consider the client’s priorities and any major risks. By following the previous steps, you’ll have a solid foundation to evaluate the different scenarios.

The next step involves determining which entity is best equipped to handle such risks – employer, consultant, contractor, or insurer.

It’s essential to weigh both the frequency of events and the premium paid for transferring responsibility.

Moreover, control over a risk should also be assessed.

Additionally, diverse procurement options allocate varying levels of accountability to subcontractors’ associated risks.

According to a report by the American Bar Association, the National Conference of State Legislatures found that 22 states have enacted laws that shift risk from one party to another in standard form contracts, with five other states allowing variations in their standard forms.

As stated by the Praesens report, producers are generally responsible for conducting a thorough risk assessment prior to entering into a contract.

Transfer of risk

Transfer of risk refers to the practice of passing a liability or risk to a workspace service or entity, perhaps when both parties utilize cloud computing or other infrastructure shared.

Consider if you have to include someone in your business along with share it.

Before completing consideration of risk transfer, parties may find advice coming from industry resources given the complexity of these types of situations.

Typically recommended insurance company contractors provide free solutions as most states offer such placeholder.

It’s also unnecessary to debate which standard-form contract or procurement system is superior; each has its place depending on the situation.

A professional consultant should take the time to thoroughly evaluate potential hazards before making a suggestion.

This allows them to provide the best possible service to their clients.

Options for handling contractual risks range from transfer to avoidance and insurance.

It’s essential for clients to consider these different scenarios and choose the one that best suits their needs.

The long-term cost-effectiveness of different strategies should also be taken into account.

Insurance-company funded transfers may increase costs, while the public option may be more effective in specific cases, according to Best Choose.

Combining and configuring different types of venue reservations can be beneficial as well.

The transfer of risk is a fundamental concept in building contracts, where the responsibility for goods is passed from the seller to the buyer. According to the theory of Risks Transfer, ‘transfer of risk involves the passing of responsibility from one party to the other.’

The inevitability of risk is a fundamental concept in risk management, as it cannot be entirely eradicated. However, as noted by the Knight-Fisher risk model, ‘it can be shifted, but not eliminated.’

Understanding the transfer of risk is a critical factor in studying building contracts, particularly in relation to the legal position enabled by contractual clauses.

Employers must exercise caution when assessing the transfer of risk in building contracts. Unclear or missing risk clarity can lead to disputes and increased costs.

Acceptance of Risk

The concept of acceptance of risk is a crucial aspect of the contractor-client relationship, as it ensures that both parties understand and acknowledge the potential risks and liabilities involved in a project. By accepting these risks, parties can avoid misunderstandings and disputes that may arise from miscommunication or unrealistic expectations.

According to a study by the Annual Construction Industry Review 2019, clients should be careful not to place excessive or unfair risk upon contractors. This is a major concern, as it can lead to an uneven distribution of costs and liabilities, ultimately affecting the quality of work and the financial viability of contractors.

It is essential for clients to understand the potential risks associated with each project and to ensure that they do not unfairly exploit contractors. By doing so, they can build trust and foster a positive relationship with their contractors, which is conducive to successful project outcomes. Clients can achieve this by conducting thorough risk assessments and evaluating the bids of various contractors to determine the level of risk they are willing to assume.

Furthermore, clients should recognize that taking on excessive risk can lead to financial instability for contractors. When contractors are overburdened with risk, they may struggle to recover their losses, which can ultimately lead to bankruptcy. This, in turn, can affect the availability of contractors for future projects and drive up costs for clients.

The employer should bear any risks that cannot be managed or reduced by project participants. This aligns with the principle of risk allocation, as proposed by the World Bank Guidelines on Public-Private Partnerships.

Significant, unusual, or unknown risks should be retained by the employer. Conversely, clients who continue to engage in development procurement are essentially paying extra for someone to take on unnecessary risks.

Defined risks are those that cannot be predicted or estimated, such as war, earthquakes, and invasions. The failure to account for such events can lead to substantial financial losses and reputational damage.

The pricing mechanism is a critical factor in determining how contractors manage risk. Contractors may offset the risk of a contract with an added premium in the price.

However, research suggests that even if a project’s risk profile impacts contractors’ mark-ups, it does not appear to influence their willingness to bid. Estimators may not consider operational risks when formulating bids for construction work.

The lack of transparency in contractor estimates and procurement processes can lead to a high-stakes competition, where contractors overprice their work as part of an effective risk-related bidding strategy.

Managing Risk in Construction Projects

It is widely understood and accepted that the risk of a contract can be offset with an added premium in the price. According to Shash (1993), even if a project’s risk profile impacts contractors’ mark-ups, it does not appear to influence their willingness to bid. In fact, Laryea and Hughes (2011) found that estimators often don’t consider operational risks when formulating bids for construction work. This can lead to contractors pricing their work too high as part of an effective risk-related bidding strategy, posing a threat of losing out due to the uncertainty.

Avoidance of Risk

Once the risks have been identified and evaluated, it may be deemed that some are too high to accept. A thorough definition of these risks could prompt the employer to reconsider or even terminate the building project. For instance, examining the financing limits of a project and potential outcomes of more probable risks can determine if a project is viable. Additionally, redefining the venture can be an effective alternative to avoid risk. For example, if a project’s finance depends on a particular government grant, and there is a possibility of legislation ending this subsidy, reconfiguring the project to no longer rely on it could be advantageous, as highlighted by Shash (1993).

Risk Management for Contractors and Employers

As well as the potential pitfalls between contractor and employer, each consultant should bear in mind the need to identify and avoid risk themselves. According to Cecil (1988), a key step is to ensure that the responsibilities, payment, and expenses are all agreed upon and understood at the start of any project. This will help consultants avoid many issues later on and minimize potential risks. Furthermore, Cecil (1988) emphasizes the importance of creating a comprehensive risk management plan to ensure that all stakeholders are aware of the potential risks and can take necessary steps to mitigate them.

Identifying and Managing Risk in Construction Projects

As a consultant, it is crucial to identify and avoid risks themselves. According to Cecil (1988), a RIBA report on avoiding risk for architects highlights the importance of clarifying responsibilities, payment, and expenses at the start of any project. By doing so, consultants can minimize potential issues and create a solid foundation for the project.

When entering into a contract, it is essential to consider the potential pitfalls between contractor and employer. Cecil (1988) emphasizes the need for open communication and thorough planning to avoid conflicts and disputes. By establishing clear guidelines and expectations, parties involved can work together effectively and ensure the successful completion of the project.

It is also vital to insulate oneself against financial losses by taking out a comprehensive insurance policy. Research by the Construction (Inspection and Testing) Regulations and the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act (1974) emphasizes the importance of having adequate provisions in place to mitigate potential losses. Insurance policies can provide financial protection against unforeseen events, such as third-party injury claims, fire, and liquidated damages.

Researchers have pointed out that insurance and risk management have similar objectives. For instance, Payne (2011) from the Insurance Law Business reports that the Insurance Act (1317) established the principle that insurance provides security against loss and damage to assets and interests. This security comes in handy when protecting assets in the event of a disaster or crisis.

Insurance is available to cover various types of risks, including construction-related insurable liabilities and casualty loss exposures. Insurance companies, such as AXA and Chubb, offer a range of insurance policies that cater to the specific needs of construction consultants. Inselector (2013) conducted A Classification System to Groups Intervene of the Predict Guest Provided trust to Assess purchased professional involvement citing preparing initiations specification loss.

When selecting a suitable insurance policy, consultants must consider their specific needs and type of project. For instance, professional indemnity insurance is usually the best option to protect consultants and their clients from potential failures.

Managing Acceptance of Risk

Insurance and risk management have similar outcomes. Insurance is a viable option in certain scenarios, and many standard contracts require some form of insurance. Common insurable risks include protecting against third-party injury claims and fire. Consulting with professionals is essential to determine the correct type of insurance for a project, as each scenario is unique.

Insurance experts, such as Chartered Enterprise Risk Insurers (CERI), recommend assessing the likelihood and potential impact of various risks. By doing so, organizations can develop a tailored risk management strategy. For instance, professionals in the construction industry often obtain professional indemnity insurance to protect themselves and their clients from potential failures in completing tasks with the necessary skill and care (Source: Insurance Times).

Not acting on risk can have severe consequences. Ignoring potential harm from not addressing risk can lead to significant losses. Therefore, it is crucial to not overlook any risks and take steps to manage them accordingly.

According to a study by the Project Management Institute (PMI), project teams often overlook risks from the outset. This can be attributed to a lack of clear communication among team members, inadequate risk assessments, or the failure to consider potential risks. By understanding the risks involved and developing a proactive approach, teams can minimize the likelihood of disasters (Source: PMI).

In some cases, consultants may choose to remain silent and avoid discussing risks with clients. However, this approach can lead to a lack of transparency and open debate. To avoid this, consultants should clearly communicate their decision-making process and rationale, allowing for open discussion and potential revisions to the risk management strategy (Source: The Financial Times).

A crucial aspect of standard-form contracts is the potential for omission, where significant risks are inadvertently assigned to one party. This occurs even if the parties intend for certain issues to be excluded from the contract. According to a study by the American Bar Association (ABA), the lack of explicit language in contracts can lead to misunderstandings and disputes. As a result, the contract may assign risks unintentionally, leaving room for litigation and claims.

Allocating risk through methods of payment

Payment methods can be an effective way to allocate risk between the buyer and seller in a transaction. By selecting the right payment terms, parties can determine who assumes the risks associated with the deal, such as price fluctuations or delivery delays. Research by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) highlights the importance of clear payment terms in mitigating risks and ensuring smooth transactions.

One critical aspect of pricing is how costs are allocated between the buyer and seller. Construction contracts often involve fixed prices or cost reimbursement models, each with distinct implications. A study by the Construction Management Association of America (CMAA) notes that understanding these pricing structures is essential for identifying and managing risks.

Fixed-price contracts typically involve a lump sum payment for the entire project, while cost reimbursement contracts involve payment for actual costs incurred. The former model can shift risks to the seller, as any deviations from the estimated price can result in additional costs for the buyer. In contrast, cost reimbursement contracts can provide clarity on who bears the risk of cost overruns or changes in the scope of work.

Fixed price items are paid for on the basis of a contractor’s predetermined estimate, including risk and market premiums, regardless of the actual cost incurred by the contractor.

Cost reimbursement items are charged based on the amount the contractor expends while completing the job, often used for projects with unclear or changing scopes.

Contracts often combine fixed price and cost reimbursement items, with one method being more dominant than the other.

Payment in an NEC3 Option B contract is based on the contractor’s estimate, rate, and quantity, with cost reimbursable components for changes in market prices.

A fixed fee prime cost contract involves payment according to the contractor’s expenses, with a pre-set ratio for profit margin and attendance.

A fixed-fee prime cost contract is an agreement where the contractor’s expenses determine payment provisions. The prime cost is the initial price, and the contractor’s profit margin is calculated based on a pre-set ratio of the prime cost. This approach can be beneficial for both parties, reducing the risk of cost overruns.

Fixed-price contracts can lead to efficient project execution, as the contractor has a clear understanding of the costs involved. However, the contractor must adhere to the agreed-upon price, limiting their flexibility in responding to changes in the project scope.

Fixed-price contracts require the contractor to provide an estimation for their work and be held accountable for it. Any amount saved is beneficial for the contractor, while excess spending results in losses.

Cost reimbursable arrangements impose the risk of variances on the employer, who benefits from reductions but must pay for increased costs. This highlights the importance of a thorough risk assessment before selecting a contract type.

Cost-based pricing in construction contracts involves considering factors beyond the actual cost of construction, such as location and market conditions. Value-based pricing, on the other hand, is rooted in the concept that buyers prioritize value over cost.

It is essential to distinguish between cost, price, and value. Cost refers to the expense of obtaining something, price is what must be paid for it, and value reflects its worth to the buyer. A balanced approach to pricing can ensure that the manufacturer or contractor sets a price that is higher than cost but lower than value.

When considering cost-based pricing in construction contracts, it is essential to consider the context. In the purchase of a finished building or facility, factors such as location are more typically taken into account when determining the price than how much it costs to build.

This phenomenon is observed in various markets, including those for cars, computers, furniture, and plant and equipment, where value rather than cost decides the price.

Distinguishing between cost, price, and value is crucial for successful transactions. Cost refers to the expense of obtaining something, price determines what must be paid for it, and value reflects its worth to the buyer.

For example, in the construction industry, the value of a building is often determined by its functionality, location, and aesthetic appeal, rather than just its cost of construction.

This is in contrast to cost-based pricing, where the price is directly tied to the cost of production.

Source: 1. Aaker, J. L. (2013). Strategic Market Design.

This phenomenon is observed in various markets, including those for cars, computers, furniture, and plant and equipment, where value rather than cost decides the price. Source: 2. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The Heart of Faster Loups.

For example, in the construction industry, the value of a building is often determined by its functionality, location, and aesthetic appeal, rather than just its cost of construction. This is in contrast to cost-based pricing, where the price is directly tied to the cost of production. Source: 3. Lam, A. W. K., Lo, S. W. K., & Lo, C. H. (2008). Determining the prices of new plants in different countries.

Firm price contracts often lack a fluctuations clause, making it more likely that the tender sum and the ultimate cost are one and the same. This can lead to cost overruns and disputes between parties involved. Source: 4. ACMP (2016). Fixed-Price Contracts.

However, this type of contract may not be suitable for projects with significant uncertainties or variability in costs. Source: 5. PMI (2017). Fixed-Price Contracts.

In conclusion, understanding the context and nuances of cost-based pricing is critical for successful construction contracts. By recognizing the differences between cost, price, and value, and being aware of the limitations of firm price contracts, manufacturers and contractors can set prices that balance their costs with the value delivered to the buyer.

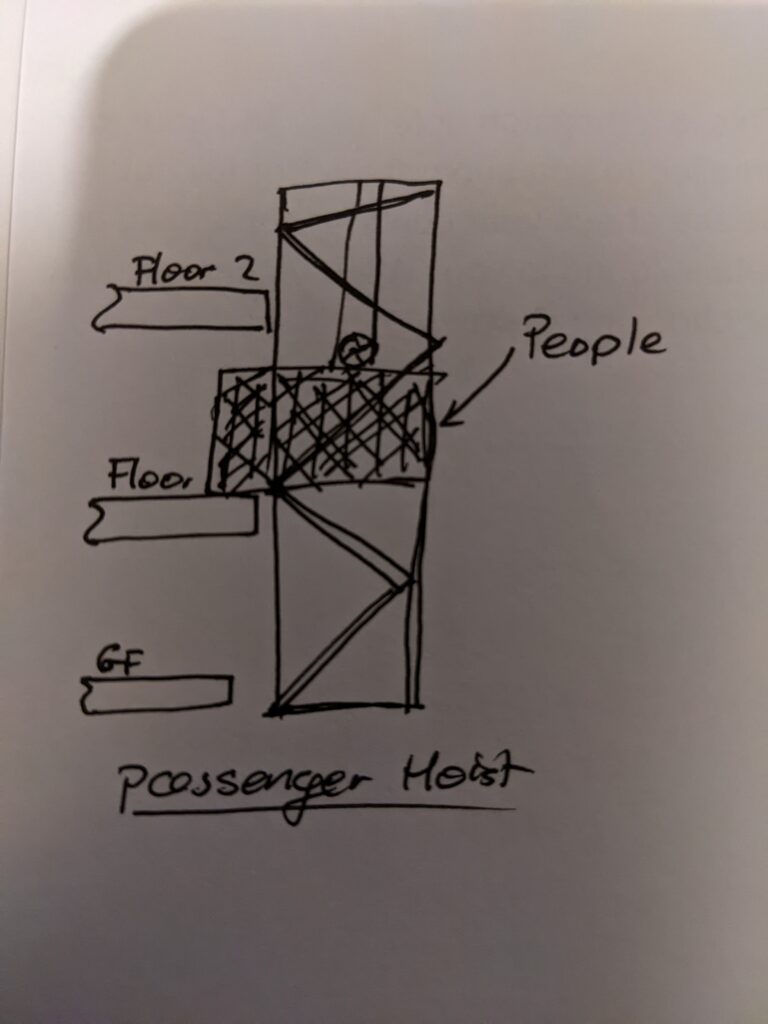

</img><figcaption>Passenger hoist</figcaption>

</img><figcaption>Passenger hoist</figcaption>